Keidanren

I. A Trade Strategy for Japan

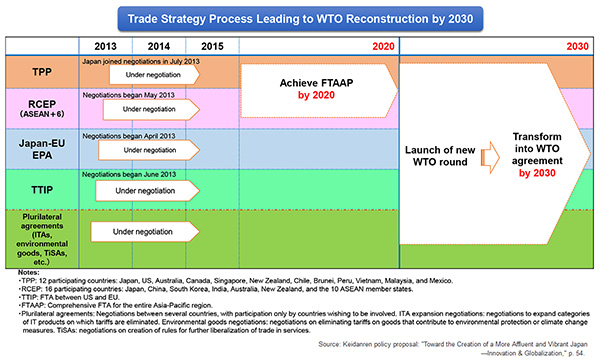

In a policy proposal entitled "Toward the Creation of a More Affluent and Vibrant Japan—Innovation & Globalization" released in January 2015, Keidanren set out a road map for the trade strategy that Japan should strive to achieve by 2030.

WTO Doha Development Agenda (DDA) that started in 2001 has stalled, and the focus of trade strategy for major countries including Japan has shifted to negotiations for mega-FTAs, such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement (EU-Japan EPA), and Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP). Considering these circumstances, in the short term Keidanren's vision concentrates on realizing such mega-FTAs as well as field-specific plurilateral agreements, including Information Technology Agreement (ITA) and Trade in Services Agreement (TiSA), and achieving Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific (FTAAP) by 2020. And also we advocate converging various agreements into the WTO agreements through a new round#1, and establishing a new high-level, multilateral free trade and investment system by 2030.

Recognizing that the WTO and its forerunner the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) have been the institutional foundation supporting the economic development of Japan which heavily depends upon trade and investment. Keidanren has consistently asserted that the WTO should be the axis of Japan's trade strategy. This conviction remains unaltered, and we are extremely concerned about the declining presence of the WTO as the cornerstone of the international economic order, with the stalemate of the DDA negotiations and the rise of mega-FTAs'.

This year commemorates the 20th anniversary of the establishment of the WTO and 60 years since Japan joined the GATT. At this important milestone, Keidanren proposes measures toward WTO reform with a view to rebuilding a multilateral free trade and investment system that will enable the WTO to once again demonstrate its value as a crucial element in the global free trade and investment infrastructure under sound governance.

|

| [ Click to enlarge ] |

II. The Multilateral Free Trade and Investment System: Issues and Direction for Reform

Keidanren advocates the multilateral trading system covering the entire world is essential for global economic growth and the WTO lies at the heart of such regime, even though governments and business communities are turning their attention to FTAs and field-specific plurilateral agreements. Below summarizes the WTO's contribution to expand international trade and investment, issues faced, and points requiring reform.

1. WTO Achievements

The primary purpose of the WTO is to curb protectionism and promote open trade for the benefit of all. In order to apply trade liberalization and rules uniformly to all WTO members under Most-Favored-Nation-Treatment (MFN) and National Treatment (NT), the WTO has three main functions: (1) Trade negotiations (liberalization and rule-making), (2) Implementations and Monitoring#2 (rule facilitating), and (3) Dispute Settlement#3 (rule enforcement), together with excellent institutions supporting these functions.

(1) Effectiveness of Implementations and Monitoring and Dispute Settlement Functions

Keidanren recognizes that the WTO's monitoring of the implementations of the agreements and dispute settlement system have contributed to function to curb protectionism in the world to some extent.

For example, many countries tightened inspections of imports from Japan following the Great East Japan Earthquake, citing fears of radioactive leakage from the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power station. However, because the monitoring of the implementations of the agreements function to encourage these countries to comply with the WTO Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (SPS Agreement) and the Agreement on Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT Agreement), these agreements served as a bulwark against countries taking measures that were not based on scientific evidence.#4

The SPS and TBT Agreements require signatories to notify the SPS and TBT Committees prior to introducing new measures or amending existing systems relating to food safety, animal and plant health, or certification standards for industrial products, and any country doubting the compatibility of such measures with these agreements and believing that the measures would have an adverse impact on the export of goods it produces may raise a specific trade concern (STC) seeking rectification before the relevant measures are put in place. The rise in the number of STCs submitted to the SPS and TBT Committees can be seen as the evidence that the system is functioning effectively.

Recent examples of dispute settlement include the decision that China's rare earth export controls and Argentina's import restrictions on a variety of products were inconsistent with WTO agreements.#5 In an effort to reach quick and fair settlements, procedures have been greatly enhanced since the GATT era through the establishment of new processes including automatic procedures and two-stage hearings,#6 the adoption of a "negative consensus" approach,#7 prohibition of unilateral measures, and the right to impose cross-sectoral sanctions.#8 Compared to a total of 314 disputes settled under GATT between 1948 and 1994 (an average of 6.7 per year), 495 disputes were settled under WTO between 1995 and February 2015 (an average of 24 per year), showing that the system is functioning effectively.

(2) Issues with the Doha Development Agenda (Doha Round): Declining Interest in the WTO and the Acceleration of Mega-FTAs negotiations

The WTO's functions of monitoring implementations of the agreements and dispute settlement are operating effectively, but it must be acknowledged that its trade liberalization and rule-making function is virtually not functioning fully. The Doha Development Agenda (Doha Round) was billed as the "development round" in an attempt to promote liberalization that would continue supporting economic growth in developing countries, yet sluggish negotiations have made little progress. Conflict has arisen between developing and developed countries over whether rules giving consideration to the needs of developing countries should be enhanced. And the Trade Facilitation Agreement adopted in November 2014 is the only agreement achieved by all WTO member during this round. Even the outlook for future negotiations is uncertain, let alone any prospect of concluding the round. Under these circumstances, Japan and other major countries are setting their sights on negotiations for mega-FTAs and field-specific plurilateral agreements rather than WTO.

(a) WTO Systemic Issues

Systemic issues inherent to the WTO are the root cause underlying the stalemate of the Doha Round. The first of these is the "single undertaking", which is predicated on reaching an agreement among 161 countries and regions in all fields of negotiation and having member countries, with certain exceptions, uniformly accept the rights and obligations of all WTO agreements. This approach has now reached its limits. The second issue is the consensus approach, which makes it difficult to reach decisions in negotiations. Agreement becomes almost impossible to achieve, since in reality the consensus approach substantially amounts to a right of veto for each of the 161 WTO members, enabling a single country to block the adoption of any measure it opposes. The third issue is the absence of any definition of developing countries and special and differential treatment provisions#9 that favor developing countries with technical assistance and exemption from or easing of agreement obligations. Since self-declaration is the basis for determining whether or not a nation is a developing country,#10 there have been cases where nations that can scarcely be regarded as developing countries have enjoyed preferential treatment even though this is clearly unreasonable. Finally, the multilateral negotiation approach, whereby 161 countries and regions negotiate en masse, impedes the progress of discussion.

(b) Negotiations Unsuited to Global Value Chains

The slow pace of negotiations mentioned above, combined with the narrow scope of talks, has led to reduced interest in the WTO among member countries, especially in their business communities.

The Doha Round negotiations have focused on eliminating tariffs levied in the course of trade in goods,#11 but as foreign direct investment and demand for global ICT services (e-commerce and telecommunications) have increased with the expansion of global value chains,#12 the priority for rules has shifted from "on the border" to "behind the border" measures.

In the ICT sector, for example, some countries—especially emerging economies—have adopted forced localization measures (FLM), such as requirements to store data locally and mandatory use of local intellectual property rights, acting under the guise of security measures but with the real objective of strengthening their technical, R&D, and production capabilities. Legal challenges to such conduct are difficult under existing WTO agreements,#13 and this situation hampers global information flows and by extension is bound to have adverse impacts on all industries. Many countries are seeking to achieve smooth cross-border flows of data and content through FTAs#14 and TiSA, but we believe that in principle WTO agreements provide the best avenue to contribute to the construction of seamless global value chains. To respond to business needs and the requirement for speed, WTO negotiations should be broader and deeper in scope. The WTO and other relevant organizations also need to take appropriate steps to achieve compatibility of national-level cyber-security measures with international rules.

2. WTO Reform

(1) The Significance of the WTO

It is difficult to imagine any FTA or similar agreement being reached in the near future that covers as many members as the WTO or functions as effectively in applying identical rules to its members. While the WTO faces some issues, its significance remains undiminished.

As corporate global value chains continue to expand, there are concerns that companies' worldwide business activities may be impeded by mega-FTAs and field-specific plurilateral agreements confined to the Asia-Pacific region and Europe, since such agreements restrict the countries and regions to which the same trade and investment rules are applied. At the same time, the different rules applying under various mega-FTAs force companies to alter their approach from one country to the next, detracting from the positive effects of FTAs and preventing achievement of the anticipated productivity improvements. Harmonization of rules is required in order to avoid such adverse effects, and the WTO is the only forum for achieving such coordination of different policies.

And also, utilization of WTO dispute settlement procedures is the only solution when a trade dispute arises between countries that are not parties to an FTA, or when protectionist measures have been taken unilaterally. For example, trade disputes frequently arise among the US, the EU, and China,#15 but since there is no prospect of bilateral FTAs or a mega-FTA including these parties being concluded in the near future, they have no option but to rely on WTO dispute settlement procedures.

Moreover, the WTO offers the only framework for effectively dealing with issues such as trade remedies and subsidies for developing countries that have been left out of the FTA competition or have fallen into the cracks between mega-FTAs. Thus, there are fears that the WTO's loss of momentum and reduced functionality could leave such countries shut out of the globalization process.

(2) Approaches to Reform

Bearing in mind the importance of the WTO as stated above, there is a need to address the challenges it faces, namely, the sluggish pace and narrow scope of its negotiations, and to implement reforms to revive and strengthen its rule-making functions, in particular, so that it can rapidly produce effective results in proactively updating existing rules and formulating new rules to contribute to business development.

(a) Post-Doha

Given that there is no prospect of concluding the Doha Round, merely prolonging negotiations will only make governments, business communities, and the general public less inclined to trust the WTO and take an interest in its activities. Keidanren proposes the WTO member should resolve remaining issues swiftly including "NAMA"#16 "Service" and "Antidumping" in post-Bali work program due to be drawn up by the end of July this year#17 and also the Doha Round should be brought to a close. There will then be a need to start examining ways of using the WTO framework to converge various agreements, including mega-FTAs and field-specific plurilateral agreements, into multilateral agreements.

(b) Rethinking Negotiation Methods: Strengthening Rule-Making Functions by Utilizing the Critical Mass Method

For post-Doha negotiations, it will be essential to rethink the consensus approach and the single undertaking, which are the bottlenecks in negotiations. In order to facilitate negotiations, there is a need to utilize plurilateral#18 frameworks and establish rules in fields not covered by existing WTO agreements or Doha Round talks (such as ICT, investment, competition policies, and environment).

Since plurilateral talks take place among willing countries and address specific fields, the countries are not bound by single undertaking constraints and can avoid current barriers to decision-making, and there is no requirement to obtain the agreement of all WTO members. Furthermore, use of WTO implementations and monitoring and dispute settlement functions can be expected to enhance the effectiveness of such agreements.

There are several styles of plurilateral negotiation,#19 but considering that trade talks demand speed, depth, and broad scope of application, Keidanren believes that "the critical mass method"#20 should be adopted, because it offers the greatest potential in these areas. Since this method applies liberalization commitments agreed by a group of participating countries to non-participating countries as well, such non-participating countries are permitted a "free ride"#21 but are also bound by the rules of the agreement.

Considering the growing influence of emerging countries on international trade and investment, however, unlimited tolerance of free riders carries the risk of fueling a sense of unfairness among participating countries and obstructing the supply of products and services to emerging markets. Thus, there is a need to carefully examine the best methods of encouraging liberalization.

There is also a need to clearly define the term "developing country" and conditions for special and differential treatment, in other words, to set up systems for establishing time limits and taking exceptional measures to the extent that participating countries can tolerate the damage caused by such measures.

(c) Utilizing the Results of the TPP and Other Trade Negotiations into the WTO Agreements

Once negotiation forums and methods are established, reaching agreement would be a time-consuming process if discussions were to start from zero-base. For this reason, the outcomes of trade negotiations for the TPP and other treaties that have a wider range of ruling compared to the existing WTO Agreements should be utilized to set up new systems. The aim should be to build a more comprehensive multilateral free trade and investment system by harmonizing these various agreements and enabling their application to all WTO member countries in critical mass method.

In tandem with such efforts, it will be essential to provide further support to developing countries through measures such as capacity-building and aid for trade, in order to make high-level agreements more acceptable to such countries.

(d) Formulating a Work Plan

To facilitate future negotiations, a work plan should be drawn up that places the issues in the public eye, promotes transparency, sets timeframes, and incorporates operating mechanisms for evaluating progress and making improvements in multiyear cycles.

(e) Convening Regular Discussions

Worldwide political support for the WTO is weak: whereas the IMF and World Bank convene annual meetings of finance ministers and central bank governors, the WTO only holds biennial Ministerial Conferences. Moreover, it convenes no meetings of high-level officials. Regular annual WTO ministerial and high-level officials' conferences should be held to display greater political commitment, rather than leaving negotiations up to working level government officials.

III. Efforts to Rebuild a Multilateral Free Trade System

1. Establishing a Comprehensive and Unified Trade Negotiation Structure in the Japanese Government

To enable Japan to lead world trade negotiations, it will be essential for the Japanese government to establish a unified structure and determine and implement strategic trade policy, so that Japan can take a consistent and strategically coordinated approach to all trade negotiations, including WTO, mega-FTAs, and plurilateral talks. Moreover in order to strengthen negotiating and dispute resolution capabilities, there is a need to broaden the range of negotiators and enhance their specialized skills, and to secure a budget for such initiatives. The Government Headquarters for the TPP, launched for the purpose of overseeing TPP negotiations, is functioning very effectively. It should be worth serious consideration of expanding the TPP headquarters as well as establishing a powerful new organization with unified government trade negotiating authority. In addition, private-sector legal and academic expertise should be utilized.

2. Keidanren Initiatives

As well as presenting policy proposals to government that appropriately reflect the fast-changing corporate business environment and raise pertinent issues, Keidanren will redouble its efforts to gather information from the Japanese government and exchange opinions with it. To ensure that the wishes of the business community are reflected when rules are made and implemented, Keidanren will also join hands with business communities in other countries to consider establishing a consultative business body that could meet back-to-back with the WTO (similar to the APEC Business Advisory Council that shadows APEC and the Business and Industry Advisory Committee to the OECD).

- We envisage that such talks would provide a forum for various negotiations and would not necessarily entail multilateral negotiations.

- The WTO encourages member countries to comply with trade agreements through (i) the Trade Policy Review Mechanism (TPRM), (ii) reports to the General Council and committees (SPS Committee, TBT Committee, etc.), and (iii) WTO reports on trade measures by G20 members.

- Quasi-judicial system for resolving trade disputes between members in accordance with WTO agreements.

- Referring to recent natural disasters in the Asia-Pacific region including the Great East Japan Earthquake, the Statement of the Chair issued by the 2011 Meeting of APEC Ministers Responsible for Trade (May 2011) declared that "We agree to refrain from taking WTO-inconsistent measures."

- In 2012 the US, joined by others including Japan and the EU, requested consultations on China's rare earth export controls and these measures were decided to be in contravention of WTO rules in 2014. In 2012 consultations were also requested on Argentina's import measures, and the measures were decided to be in contravention of WTO rules in February 2015.

- The process from panel establishment (equivalent to a stage one hearing) to report issuance must be completed within nine months, and the process from Dispute Settlement Body (DSB) report adoption to DSB authorization (equivalent to a stage two hearing) must be completed within 90 days.

- The DSB must approve decisions to establish panels, reports, and retaliatory measures unless there is a consensus against it.

- A system enabling sanctions or retaliatory measures to be imposed on sectors other than the sector under dispute.

- Special and Differential Treatment: (1) easing of trade liberalization obligations under WTO agreements in consideration of socioeconomic circumstances in developing countries, and (2) preferential tariff treatment when developed countries import goods produced by developing countries (exceptions to most-favored-nation rules).

- The term "developing country" is not defined in WTO agreements. Since determination of developing countries is based on self-declaration, nations such as the Republic of Korea have been treated as developing countries.

- Investment, competition, and transparency in procurement were deleted from the agenda at the 2003 WTO Ministerial Conference in Cancún.

- Cross-border chains of activity encompassing not only the production phase, but also upstream activities including product planning, R&D, and design, and downstream activities such as logistics management, sales, and customer service.

- National treatment rules under GATT Article III, TRIM Article 2, and GATS Articles VI, XVI, and XVII are thought to provide insufficient grounds.

- Rules for creating a favorable e-commerce environment, including equal treatment for digital products, are under discussion in the e-commerce segment of the TPP negotiations. (Source: Document on the TPP negotiations prepared in March 2015 by the Government Headquarters for the TPP, Cabinet Secretariat: http://www.cas.go.jp/jp/tpp/pdf/siryou/150312ver_siryou.pdf [in Japanese])

- Of the 32 complaints lodged against China since it joined the WTO, 22 were submitted by the US and the EU. All 12 complaints submitted by China were against the US and the EU.

- Non-Agricultural Market Access

- As determined by the WTO General Council in November 2014.

- "Plurilateral" is used here in the sense of negotiations among several countries, including concepts such as regional trade agreements and sector-specific plurilateral agreements.

- The three main styles of plurilateral negotiation are: (1) Critical mass method: when the volume of goods or services subject to negotiations by participating countries reaches a certain proportion of world trade (90% is the target in the case of tariffs), tariffs and/or rules applying to the relevant field are eliminated or harmonized and the results of the agreement are shared among all WTO member countries, including countries not participating in the negotiations (example: ITA). Legal basis: Article XXVIII, GATT 1994, and Article XXI, GATS. (2) Plurilateral agreement: several countries negotiate within a limited field, and any agreements reached are restricted to the negotiating countries (example: Government Procurement Agreement). Legal basis: Article X, Paragraph 9, The agreement establishing the WTO. (3) Regional trade agreement: bilateral or regional agreement that sets certain conditions effectively eliminating barriers to all trade within a region, committing not to raise barriers outside the region, etc. Effectively the same as (2) above (examples: FTAs, EU). Legal basis: Article XXIV, GATT 1994, Article V, GATS.

- The critical mass approach used in multilateral forums needs to be examined flexibly.

- For example, a country not participating in the ITA can export a given IT product to a participating country free from tariffs, yet is not obliged to eliminate its own tariffs on the relevant product.